The transatlantic journey of central heating and cast iron radiators.

Central heating and the cast iron radiator developed during a period of frenetic creativity, scientific discovery and rapid industrialisation. Our history of heating takes us from the elephants of Regent’s Park to the financiers of Wall Street, highlighting how cast iron built a global empire and how steam shaped the New York skyline.

1792

Poultry and Pineapples

The principle of central heating developed from an artificial egg incubator designed by a French farmer.

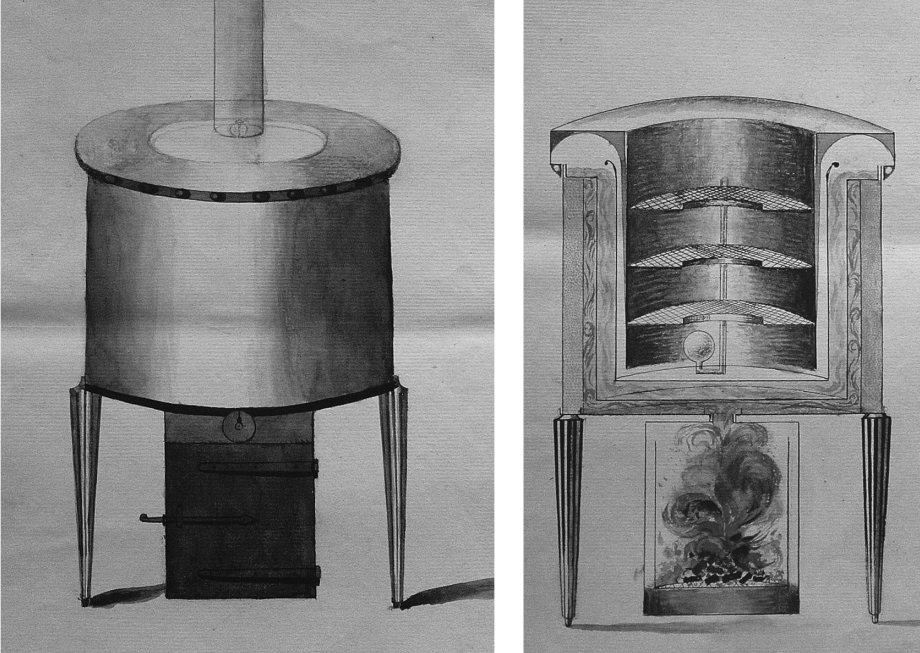

Engineer and chicken farmer Jean Simon Bonnemain invented a method of regulating heat which he used to design egg incubators and study the hatching process.

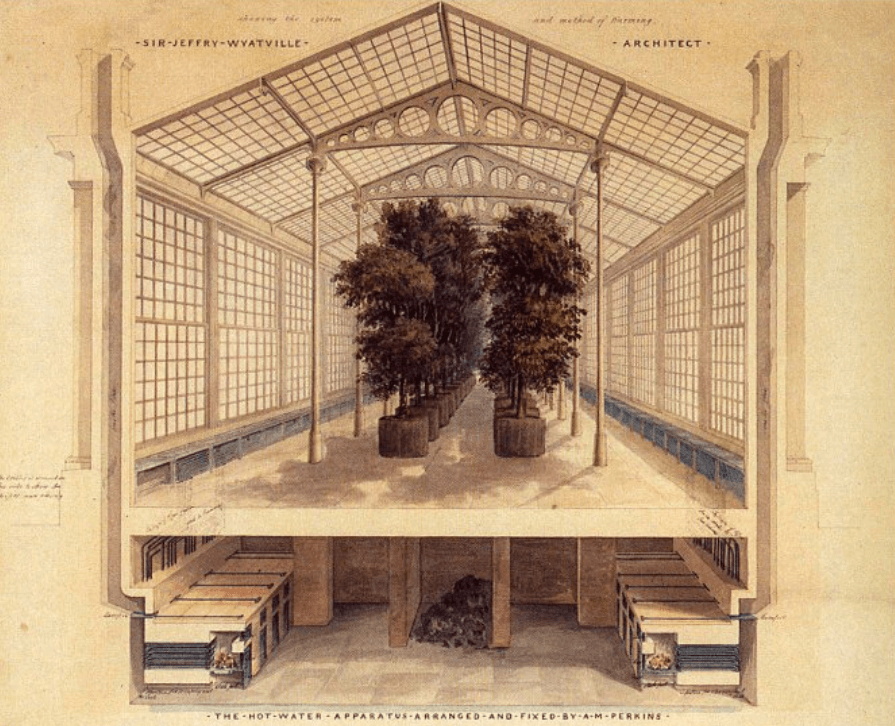

Bonnemain’s gadget was refined and taken to England by the Marquis De Chabonnes, who adapted the technology to heat The Orangery at Windsor Castle in 1829.

Homegrown exotic plants such as palms, citrus trees and pineapples were highly aspirational status symbols in Britain at the time. Only the wealthiest households could afford the luxury of heated glasshouses.

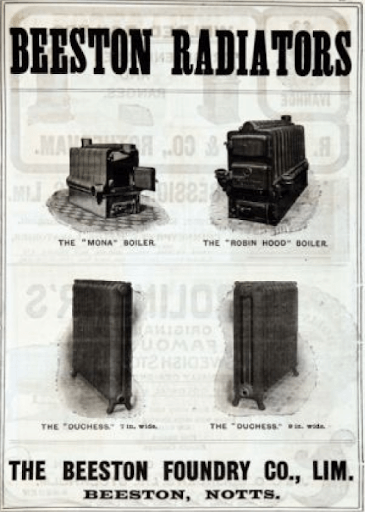

Both steam and hot water systems were used and some of the biggest names in the domestic heating industry came from horticultural origins, including the Beeston Boiler Company and Hartley & Sugden (who later installed boilers in Buckingham Palace).

1831

An American In London

Heating comes to the home thanks to a Massachusetts-born inventor working in Clerkenwell, London.

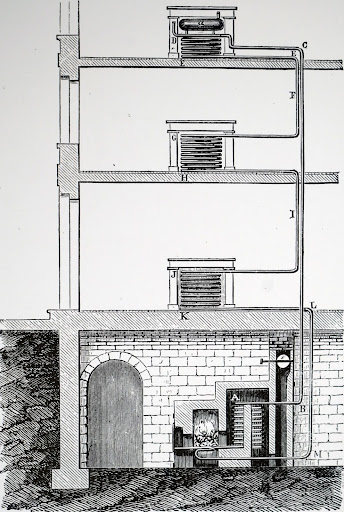

Progressing the ideas of his father Jacob, Angier March Perkins created a hydronic heating system composed of pipes coiled inside a furnace which delivered hot water at high pressure all around the house, with more coiled pipework fixed to the walls forming the ‘heaters’.

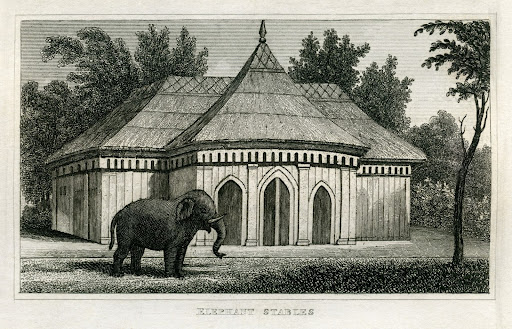

The first Perkins system was installed in a hothouse in the grounds of Hurlingham House, now London’s famous polo club. The Exotic House at Kew Gardens and the Regents Park Elephant Stables were other early installations.

The Perkins System became the first central heating to appear in domestic homes, albeit only the most wealthy. It was not only expensive to design and install but also required permanent staff to monitor the pressure and run the furnace.

An expensive yet volatile addition to the home, it was both loved and feared. Household furniture touching red hot pipes could start fires and boiler explosions were frequent due to the pressure! As Perkins gradually refined the system it became much safer and widely recognised.

1837

Another American in London

Perkins’ protégé arrives in London from the US, he would later bring steam heat to the White House.

Engineer Joseph Nason travelled to London from Boston to study with Perkins. He spent several years with the company overseeing many installations before taking his knowledge back to the States. In 1841 he installed America’s first hot-water system in a Massachusetts textile mill.

But Nason was a big believer in steam and began inventing, patenting and installing his own steam heating equipment. Selling the idea wasn’t easy given that industrial steam boiler explosions were commonplace.

Nason persevered, however, and made huge advances in the technology. By 1855, Nason had proven his expertise through several successful systems and was contracted to install steam heating in the White House.

The tallest building in the United States at the time was Manhattan’s Trinity Church, with a spire of 85m (279ft). But reliable, and increasingly sophisticated steam heating enabled the city to build higher.

Now remembered as the grandfather of steam heating, Nason laid the foundations for the New York skyline to surge upwards at the turn of the century, ahead of the fully steam-heated Empire State Building in 1931.

If your steam radiators need some attention or you’d like to add energy saving temperature controls, book a visit with one of our team. Our case study on Monroe Street shows how we helped to bring evenly balanced steam heat to a Brooklyn Brownstone home.

1854

Steam Heat for All

Stephen Gold’s safety valve makes home heating safe and affordable.

In 1854 Stephen Gold’s ‘mattress’ radiator, equipped with a safety valve, meant steam systems could operate on lower pressures and be automatically regulated without constant maintenance. In its essence, after there was enough steam to fill the radiator, the pressure would lift the safety valve up, directing surplus steam to a condensing chamber where it converted to water to be recycled back to the boiler. Gold’s motivation for the invention was that his mother suffered with ill health and the safer, more affordable heating system meant she could endure the winter months in Connecticut and avoided having to travel south.

1872

The Cast Iron Radiator, icon of NYC

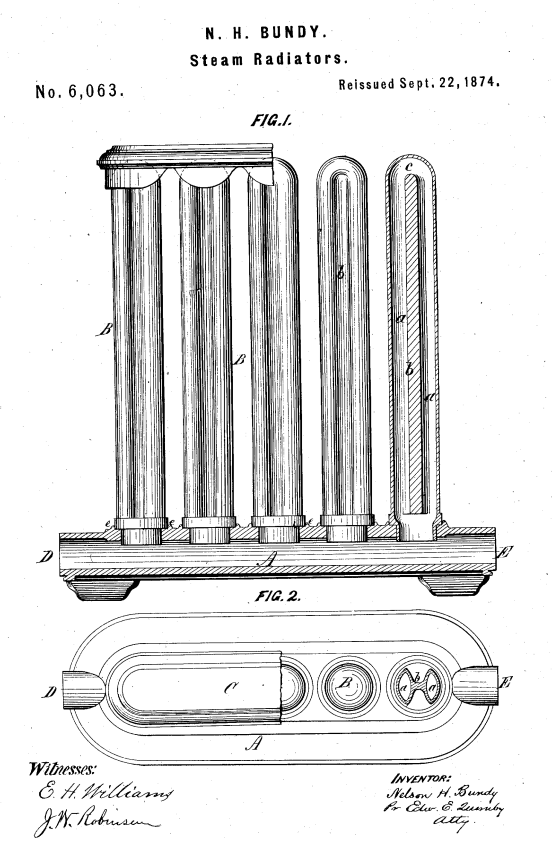

New Yorker Nelson Bundy patents his cast iron ‘Bundy Loop’ which is still going strong.

The cast iron Bundy Loop revolutionised the market. Unlike earlier wrought iron designs – Bundy’s oval, looping tubes, along with a ‘web’ of iron between each pipe, yielded a larger heating surface, making it the most efficient radiator of its time.

One hundred and fifty years later, we still find these remarkable inventions in perfect working order. Pictured is one we came across in a client’s home in Brooklyn Heights.

1888

Fancy Goods

The first ornamental radiators were alight with scrolls, foliage… and flames!

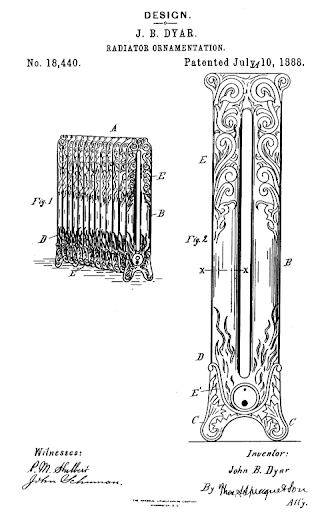

Improvements in casting techniques allowed for more detailed moulds. In 1888 John B. Dyar patented a design for “Radiator Ornamentation”, borrowing from the traditional motifs of the Pennsylvanian stove makers who were leaders in the craft.

Like many of the designs that followed, Dyar’s featured flames rising from the feet. The Bundy ‘Pyro’ even added plumes of smoke. There’s something bizarre about these designs today, but back then it was a clever way of promoting radiators as the ‘clean’ new technology to replace ‘dirty’ coal fires.

1892

Founding of The American Radiator Company

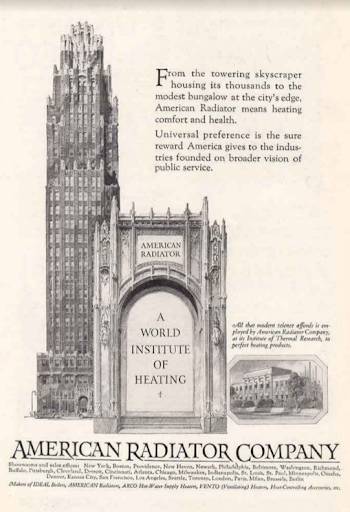

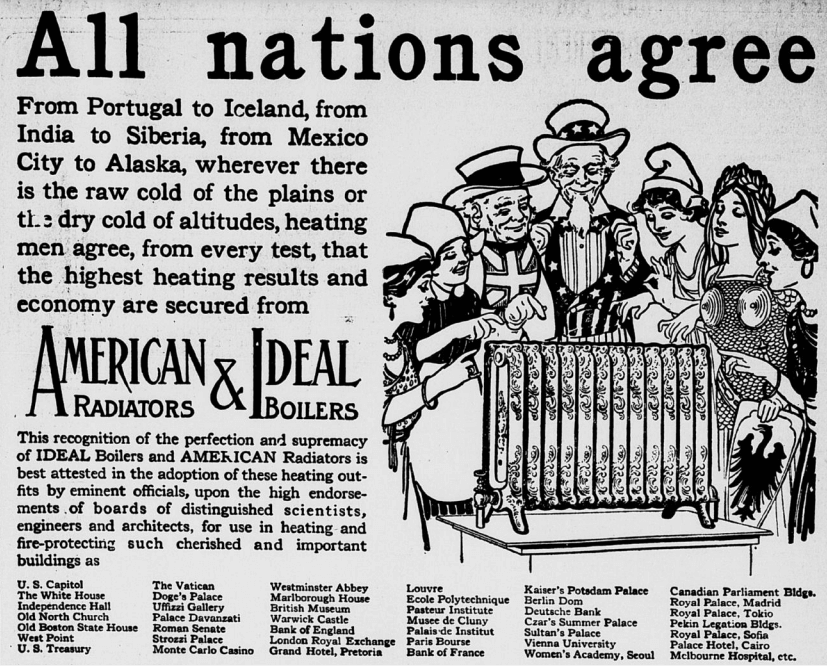

Three companies merge in the first step towards a multi-million-dollar international empire.

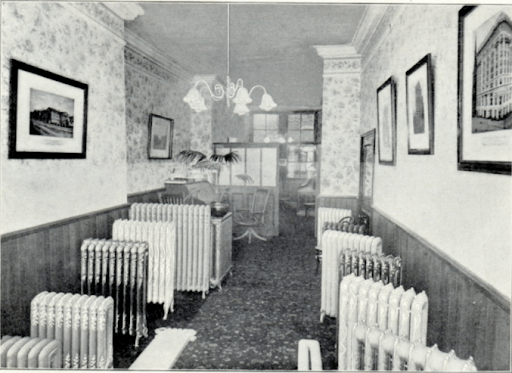

The American Radiator Company was founded in 1892 after the merger of three big players in the trade: The Detroit Radiator Company, The Michigan Radiator & Iron Manufacturing Company and Pierce Steam Heating. The company made $400,000 ($13m in today’s money) in its first year. And expanded to Europe in 1894, establishing a London showroom on Oxford Street in 1895.

In just seven years the company became the largest boiler and radiator manufacturer the world had seen. The founders of the company were John B. Dyar with his brilliant ornamental designs, scientist John B. Pierce, who also founded an important public health research institute, and Clarence Mott Woolley, an industrialist whose power and influence in his era has been likened to that of Bill Gates and Steve Jobs in theirs.

1896

The Rise of the Machines

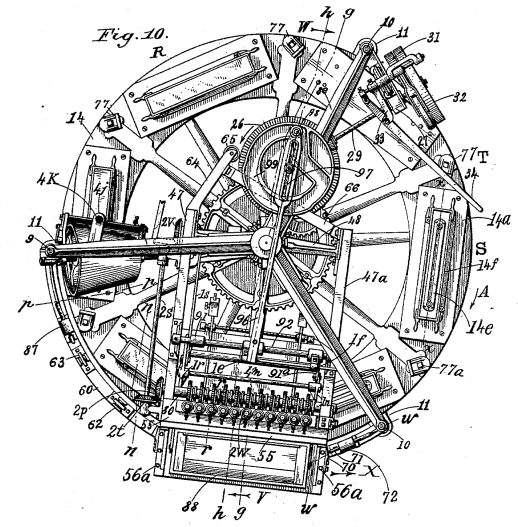

The Bryant Moulding Machine allows ARCo to scale up production and improve quality

Until this time, casts were made by workers who pressed patterns into a flask filled with fine sand. These patterns would imprint the design onto the sand before being removed to allow molten iron to fill the cast and to make the final product.

In 1895, an exhibition at the Bryant Iron Works, Niagara, displayed the revolutionary Bryant Moulding Machine. The creator, Orrin Bryant, had been working on the machine for The Pierce Steam Heating Company, before the merger in 1892.

An article written at the time writes that ‘It does the work of the human better than the human could possibly do it, and with a rapidity that is marvellous’.

Mechanising the process allowed 2,500 casts to be made every 10 hours, compared to a skilled workers 30. Mass production on this scale allowed ARCo to set a new standard in foundry technology and turbo-charged their expansion.

1899

The Empire Strikes Gold

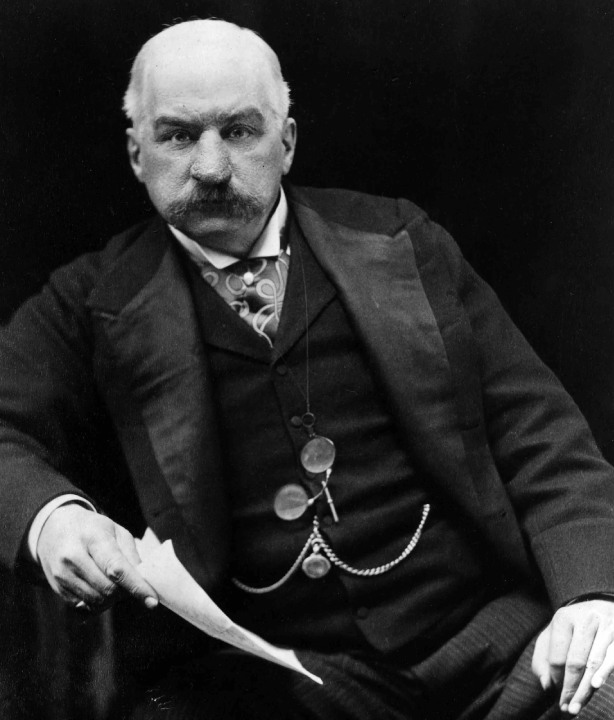

J.P. Morgan helps ARCo to monopolise the radiator market

After monitoring the success, stature and rapid growth of the company, renowned financier J.P. Morgan became interested. He administered the purchase of several of The American Radiator Company’s competitors to form one of the largest companies in the world. It wasn’t long before they were making yearly sales of $187,000,000 – the equivalent of $3.2bn today.

As they grew, ARCo invested in their own thermal research institute based in Buffalo, New York. Their financial and industrial heft drove their technology to become highly sophisticated in a very short space of time. Just as today Google, Apple and Amazon are driving the development of smartphones, computers and the internet of things, ARCo was the Big Tech of the early 20th century.

1906

A British Home for an American Corporation

ARCo set up their super foundry in Hull, England

Since beginning to trade internationally in 1895 from their Oxford Street office, and establishing foundries in France and Germany, ARCo’s sales boomed across Europe, Britain and the world.

This sparked a flood of competition from British brands, like Nottingham’s Beeston Boiler Company and Sheffield’s Longden, Walker and Co, who were now designing and casting their own models.

ARCo could not compete with locally-made radiators on price or lead times while still importing their goods from abroad, so the time came to set up shop in Britain. Close to the North Eastern Railway lines and the docks for foreign shipping, they selected Hull, East Yorkshire to build their enormous foundry.

By 1915, the company’s reputation was sealed with ARCo radiators heating Westminster Abbey, Warwick Castle and Leicester Cathedral.

Read our case study about our restoration of Leicester Cathedral’s 150-year-old ARCo radiators.

1929

Monuments in Black and Gold

ARCo build their London HQ, echoing their extraordinary Manhattan home

Firmly established as a manufacturing titan, in 1924 ARCo completed the American Radiator Building, an imposing edifice on West 40th Street, overlooking Bryant Park in New York. The building is faced in black granite and brick, to represent coal, and topped with golden pinnacles like glowing embers.

Five years later, they commissioned the same architect, Raymond Hood, to build Ideal House on Argyll Street, London, opposite Liberty’s department store. The distinctive Art Deco block has a black and gold facade directly influenced by its Manhattan counterpart.

1976

70 years of manufacturing in Hull

The foundry in Hull continued producing radiators until 1976, but cheap steel panels came knocking

In 1935 the foundry was mechanised. Standard Sanitary produced cast iron bathtubs alongside ARCo’s radiators and boilers, with another factory on the same site making porcelain bathroom wares.

By 1953, the US-owned Standard Company had taken over the entire works, building a brand new Thermal Research Laboratory. The site now covered 90 acres. They also began making sheet steel products including panel radiators.

By 1976 Stelrad Group had acquired the boiler and radiator lines. Cheaper to produce and designed to have a far shorter lifespan than cast iron, steel panel radiators were significantly more profitable.

Stelrad eventually ended cast iron radiator production, allowing panel radiators to dominate the market and become the conventional choice across the UK.

1992

The Lost Art of Steam Heating

A seminal book rekindles our appreciation of original radiators

In 1992, steam heat guru, Dan Holohan, published his book The Lost Art of Steam Heating in which he expresses his awe-inspiring sense of ‘time travelling’ while working on these centuries-old systems. ‘History you can put your hands on,’ as he puts it.

Holohan’s book also divulges the secrets he has learned while undoing years of bodged fixes and alterations. We keep copies handy in every Castrads showroom.

2018

Castrads North America

Castrads North America opens in Brooklyn and Manhattan

At Castrads, we respect the pioneering engineers that came before us with our mantra of restore first, replace second.

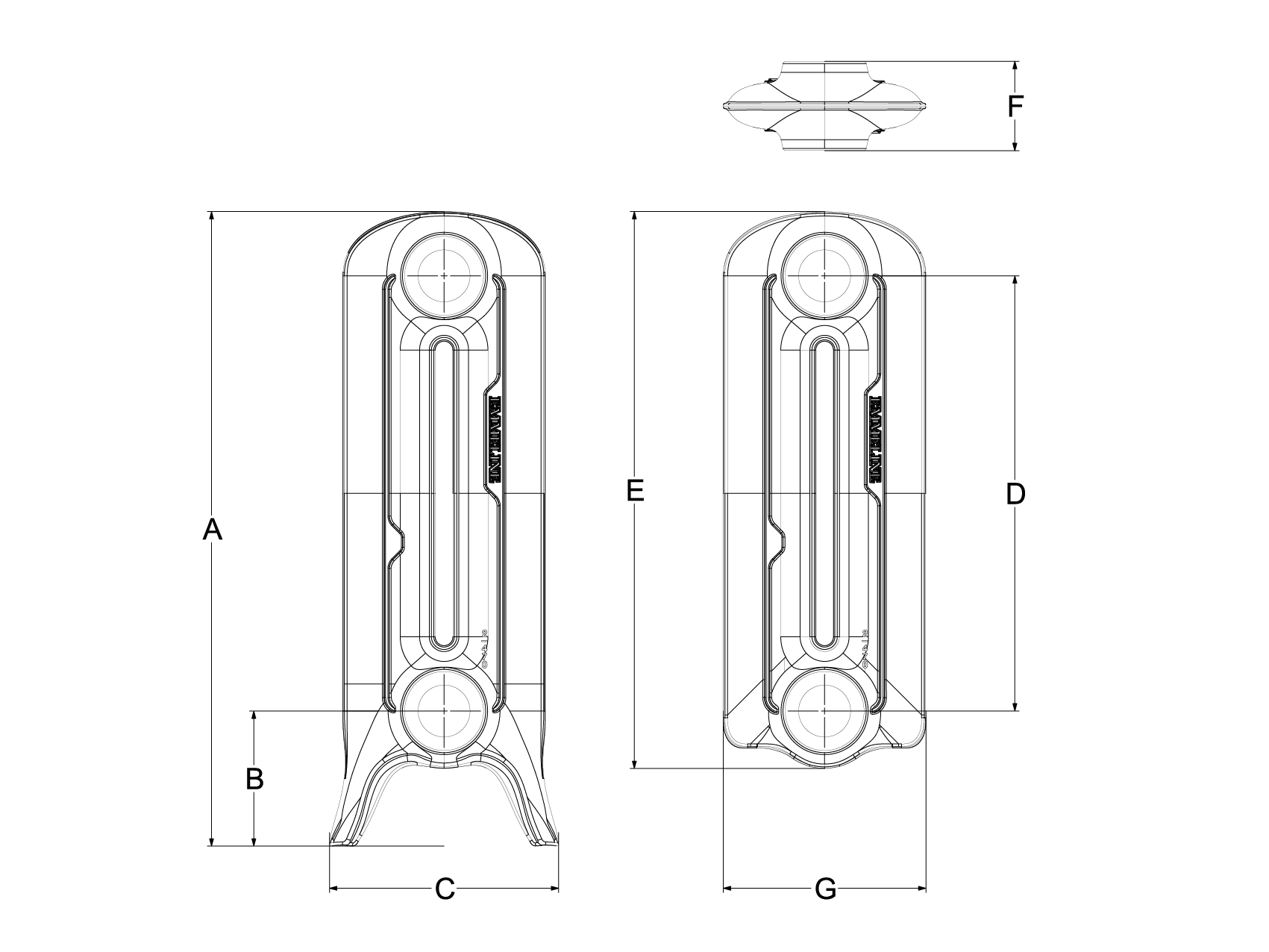

Our new cast iron radiators – which we’ve been making in Manchester, England, since 2006 – are made by the same time-tested methods as those originals and will last for centuries.

We opened in the heating museum that is New York City in 2018, where our mission is to bring the heating systems of the Gilded Age up to the standards required in our climate-sensitive times.

We aim to minimise unnecessary sales of new radiators when we can instead restore, add temperature control to existing systems, and work with heating engineers to transition away from gas and toward low temperature, heat pump-powered central heating systems – all while maintaining the aesthetic and materials that we believe are the best fit for the historical homes they heat.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dan Holohan, Victoria Dengel, Karin Taylor, Angelo Vigorito and all at the General Society of Mechanics & Tradesmen for their help in the creation of this timeline. Now based in Midtown Manhattan, The General Society was founded in 1785 by the skilled craftsmen of New York City. It is home to a Mechanic’s Institute and the second-oldest library in NYC. Tune into their wonderful lecture series here.

-300x200.jpg)